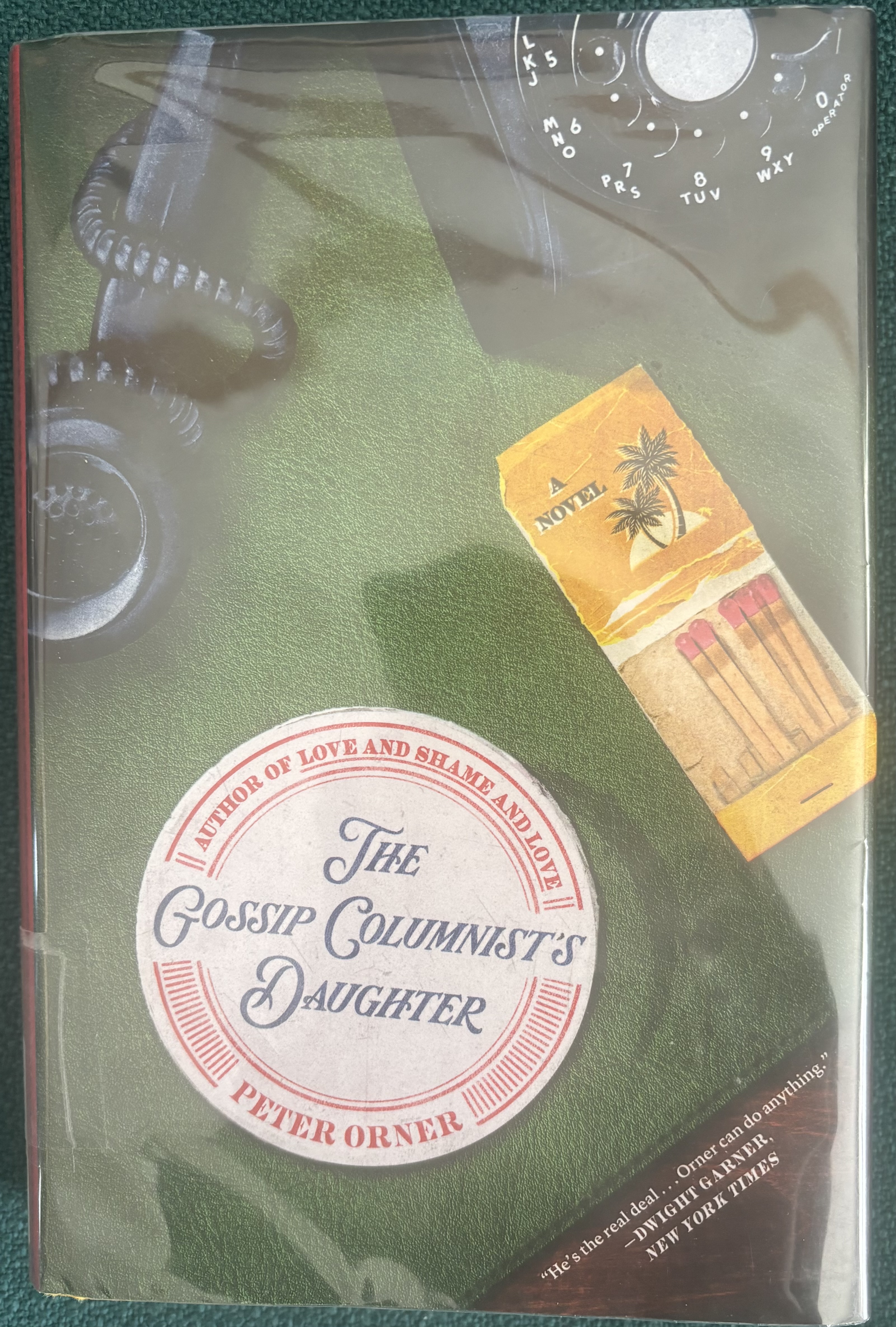

The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter

Peter Orner’s latest novel–The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter–is so good, I wish I hadn’t read it. So I could enjoy the first-time experience of reading it again.

It deals with a subset of Chicagoans from the last half of the last century—relatively prominent Chicago Jews, orbiting around a political universe controlled by Mayor Richard J. Daley, a human deity who was most definitely NOT Jewish. Though that didn’t keep them from worshiping him.

The brightest star in this universe is Irving Kupcinet, better known as Kup, who wrote a gossip column for the Sun-Times and hosted a weekly TV talk show, which apparently a young Orner routinely watched. As I did.

Orner’s plot focuses on the death of Cookie, Kup’s daughter, a Hollywood starlet, who either committed suicide or was murdered in 1963, a few days after JFK’s assassination.

Can’t be sure how Cookie died as the truth's probably concealed by powerful operatives protecting the interests of other powerful operatives. Like a smaller version of the Kennedy assassination, which, of course, has its own connection to that constellation of 20th century Jewish Chicagoans–Jack Ruby.

Bravo, Peter…

In the world Orner depicts, everyone's corrupt, everything's rigged and only a dumbass, who swallows the bullshit the newspapers feed them, would think the system’s legit. You might say little has changed in the last 60 years.

The writing is delightfully elliptical. Sometimes Orner uses quotation marks, sometimes he doesn’t. He moves back and forth through time and perspective, often from one sentence to the next. But if you keep up, man, what a ride. Give you one example…

Kup and his best friend, Lou, are in the locker room at the Standard Club, a private club for upscale Jews, and something in that moment triggers Lou's memory of a road trip they took 30 years before…

Irv points toward a swamp to the west of the road.

Out there, he says. See it? They call it Wolf Lake.

What about it?

It’s where they dumped Bobby Franks in a culvert.

Oh, Lou says and feels it in his chest. Good god, I remember.

Little Bobby Franks in his little gray suit.

To be a Jew in Chicago at that time. It was as if every Jew in the city took turns clubbing Bobby Franks on the head with a chisel.

Wasn’t the kid Leopold’s cousin?

Let's go for a walk, Irv says. Cain said to Abel.

You said it.

Did you know they stopped for sandwiches? While the kid was dead in the car. They stopped for sandwiches.

Sandwiches?

They didn't say anything after that. That way Irv and Lou used to have of talking without talking.

The Nash hurtles forward, wives in the back seat, giggling. A weekend at the beach without the children.

And then–boom–they’re back at the Standard Club 30 years later.

Lou sits on his damp towel.

Men dressing, men undressing.

Irv’s voice. Honorable Judge Holzer? How’s business, Reggie?

Splendid, Kup! Yourself?

That’s how it goes, right? When you’re so lost in your memories that everything around you vanishes and it’s like you enter a portal to the past. And when the reverie snaps, and you’re back in the present, you realize all those years flew by almost as instantaneously as Orner’s transition.

That’s what he’s saying without saying it. And a bunch of other things too, once you know who Judge Reginald Holzer is. And Bobby Franks. And Leopold and Loeb. Look them all up—also Sidney Korshak. He plays a key role in the story as well. I could identify these people for you, but it’s so much more satisfying to discover who they are, and how they fit into Orner’s themes, on your own.

The whole book’s like that—a seamless trip back and forth in time. With so much said without him saying it.

Buy it, or borrow it from the library, and enjoy the ride.